The Rolling Stones

Why Do The Rolling Stones Feel Like Our Last Legend Band?

By Joannie Penderwick

If it fits the rock ’n’ roll archetype, The Rolling Stones have probably done it.

At one point, they lost their way—dabbling in disco (Emotional Rescue, 1980) before wisely veering back toward the blues-infused rock ’n’ roll that defined their 1960s launch within London’s club scene. They endured a textbook lead singer/lead guitarist spat when Mick Jagger cut a solo album (She’s the Boss, 1985) that led to him and Keith Richards barely speaking by the time they made 1986’s Dirty Work. They were the bad boys Melody Maker warned you about, and it meant you would follow them anywhere. And that name—doesn’t it sound like the name of a band big enough to shape a subculture?

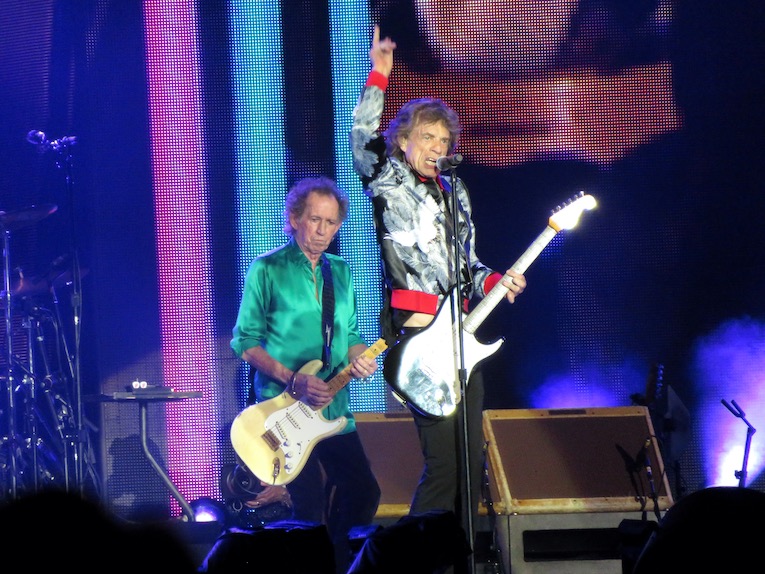

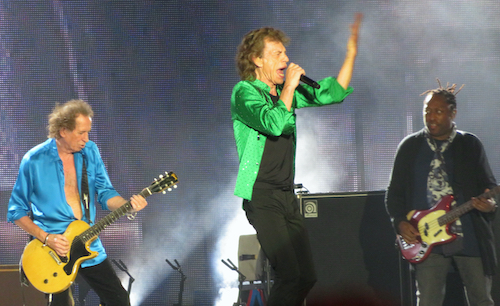

The Rolling Stones—Jagger, Richards, Ronnie Wood, and the late Charlie Watts—didn’t burn out after their fifteen. Nor did they stick around for the dubious veneration of becoming rock’s favorite granddads. The Stones’ renown circa 2021 is a fluid enough continuation of their heyday to put them in almost singular category. It’s hard to think of any other active group in rock who feel legendary in the way the Stones do.

Part of this, of course, can be credited to simple longevity. Whenever mainstream rock suffered a mood swing, The Stones didn’t get left behind or even stay the course, exactly. They adapted their core sound so it could survive.

There’s no doubt The Rolling Stones have always had their collective gaze on being the biggest band around and making it long-term, but they didn’t achieve these goals, as some bands do, by committing to rock’s (safe) middle path.

Instead, The Stones have achieved their aims through an intense focus on both their rock ’n’ roll roots and the incorporation of contemporary elements, a combination that was more or less guaranteed thanks to the complementary musical interests of Richards and Jagger. This can even be seen on an album like 1973’s Goats Head Soup. It never had a snowball’s chance of competing with Sticky Fingers or Let It Bleed, but its sax-embellished balladry and wah-wah pedal distortion and Leslie speaker signified a band intent on adapting. They’ve never been trying to artistically preserve a dead era, which even many newcomer rock acts could be accused of.

While their music itself is a huge part of their longevity, and moreover their legend, we all know there’s more to The Stones than filthy urban blues-rock jams. Their extracurricular elements—their air of perpetual teenage rebellion, their blustering insolence, their intent to consume the smorgasbord when it came to drugs and women, their modern-day pirate coutre—also made a splash. All of the above became more embedded in rock ’n’ roll mystique because of the Rolling Stones.

The Rolling Stones

Perhaps part of the reason The Stones feel like such legends is not simply that they were big—plenty of rock bands were—but that they created a template. No other band would prove able to embody the rock ’n’ roll habits and accoutrements like The Stones, but hordes would try. In fact, you could look at what we saw with the shirtless, crotch-thrusting, big-hair direction of rock in the ’80s as a campy exaggeration of the template established by The Stones. The ’80s represented a generation of affable bad-boy rockers, but The Rolling Stones hit that sweet spot first and most effectively.

No matter how many times The Stones were imitated in style and musical substance, not even Guns ’n’ Roses or Motley Crue could reproduce the sense of real danger that always roiled just beneath the surface of the Rolling Stones’ reputation.

Their short but powerful 1969 album Let It Bleed, bookended by some of the most memorable songs of their career, came out just before they headlined the Altamont Speedway Free Festival. Jefferson Airplane, Santana, and Crosby, Stills, & Nash would all perform at “Woodstock West” on a stage reportedly guarded by a detail of Hell’s Angels—but The Stones would be the main attraction. Even so, what happened off stage steals focus when the festival is remembered: someone was stabbed, there was a hit-and-run, someone on acid drowned in an irrigation canal. The event, never unexciting, was ultimately unsafe.

The fact that it was looked at as a disquieting coda to the hippie era—so associated with The Beatles—is only appropriate when you consider how The Rolling Stones landed their first record deal largely for being seen as the “anti-Beatles.” That the 1970 documentary Gimme Shelter heavily incorporated footage of the festival suggests just how associated with the Stones that danger at Altamont was.

In fact, in some ways, it seems an encapsulation of who they are as artists: they are all about the rock, and the rock is pretty great, but they’re also about sex, drugs, and a laundry list of criminal behavior. And while barely contained (in some cases, uncontained) danger seems to be a tentpole of the Rolling Stones’ legend, it isn’t the main reason their name will long be inserted into wistful sentiments of how they don’t make ’em like that anymore.

The main thing, the differentiating thing, about The Rolling Stones is that they have always struck that rare balance of aggressively turning over the old ways while making it appear that their own ways never age. No matter what has come their way, they’ve adapted; never has this been more evident than in their continuing to tour, with Steve Jordan as drummer, following the death of their long-time bandmate Charlie Watts.

But the reason you should listen to the band still today, and catch them in concert if you can, was summed up efficiently by Watts when asked why he ultimately chose to join the band: “The Stones were great.”(1) And nearly six decades later, they still are.

1. Janovitz, Bill. Rocks Off: 50 Tracks That Tell the Story of the Rolling Stones. St. Martin’s Press. 2003.

Leave A Comment